|

Piece of original Miami endangered: West Coconut Grove's Black history slipping away

BY ANDRES VIGLUCCI

A few years ago, when sisters Nichelle Haymore and Shanté Haymore-Kearney came home to tend to their roots in Coconut Grove's seminal 130-year-old Black enclave, it was to a neighborhood far diminished from the days of their youth.

Virtually all the places they'd known had gradually vanished, along with many of their old neighbors and friends. Gone was Jack's, where they would go for hot dogs after school. Gone, too, were all the other shops, restaurants, bars and clubs that once lined Grand Avenue, the heart of the neighborhood. Most of the "concrete-monster" apartment buildings that were full of people, activity and, sometimes, turmoil, were torn down or stand derelict and half-vacant.

Even the treasured cottages and single-family houses that nurtured the dreams of several generations of working-class and middle-class families like the Haymores, were disappearing. One by one, they are being demolished and their lots left vacant by real-estate speculators, or replaced - slowly at first and more recently in accelerated fashion - by million-dollar-plus white pillbox homes built by gentrifying developers. The few remaining residents, who could never hope to afford living in one, deride them as "sugar cubes."

"Our memories of walking and going places like Jack's, all of those places are gone," Nichelle Haymore, who is 48, said wistfully in an interview. The conversation took place in a Starbucks in downtown Coconut Grove, the commercial center of the far more affluent, mostly white section of the neighborhood.

There is - literally - nowhere to meet in the historically Black section of the Grove where she grew up and which, after a long absence, she again calls home. It lies just a few steps away from the Starbucks, across the persisting, if increasingly porous, racial demarcation line that has long split the neighborhood.

Once a vibrant, close-knit community, shaped and scourged by racial segregation, the storied, historically Black Coconut Grove is peopled by a singular, multi-generational mix of Bahamian immigrants and African American Southerners who played key roles in the building and cultural identity of Miami. The neighborhood is, in the brief chronicle of a young city, as foundational as they come.

And it's now on the brink of extinction.

REAL-ESTATE SPECULATION RAMPANT, DETRIMENTAL

Beset by generational turnover, decades of disinvestment and official neglect, and stubborn poverty - all in large part a product of racial discrimination, activists and longtime residents say - the neighborhood is now being swept away by what residents and the critics describe as an especially aggressive wave of real-estate speculation and residential redevelopment.

It has decimated the historic neighborhood's physical fabric and its lush, tree-shaded streets, not to mention its Black and predominantly low-income population. Its original houses, buildings and its people are being rapidly replaced by affluent, overwhelmingly non-Black new residents and their lot-filling, white-cube homes, luxury condominiums, duplexes and townhomes, residents and activists say.

"It's crazy man, all these big condos," said Rose Gore, 63, a member of a large, prominent Grove family of Bahamian extraction, as she sat at a folding table under a giant old banyan tree in front of her ramshackle rental duplex, playing Deuces Wild with an old Grove friend, Shirley Small, who was visiting from her new inner city abode in Brownsville.

All around Gore and Small, treeless, boxy white-concrete homes, gleaming new or under construction, seemed to glower over the narrow street, much of it still shady and overgrown in traditional Grove fashion.

Luxury homes and townhouses with rooftop gardens rise along what was once a street of modest homes in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Friday, June 17, 2022. The Black community is rapidly disappearing amid gentrification. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Luxury homes and townhouses with rooftop gardens rise along what was once a street of modest homes in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Friday, June 17, 2022. The Black community is rapidly disappearing amid gentrification. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Gore said she, too, will likely soon be gone. Her landlord told her a big rent hike is coming that she and her partner can't afford. Given Miami's severe housing crisis, she fears she'll end up in a shelter.

"You can't find a place to live. Ain't nowhere we can go," Gore said. "The Grove is gone. It's gone. The old days ain't never coming back. And those were good days back in the ‘70s. Lovely."

If she does go, Gore will join a massive exodus from the neighborhood - known to outsiders as West Grove, but just plain Coconut Grove or the Grove to its denizens, who make little distinction between its historically Black and its predominantly white halves.

The Grove's Black population, which once numbered in the tens of thousands, is down to a fraction of that. According to an analysis of U.S. Census figures by the University of Miami law school's Center for Ethics and Public Service, which works with West Grove community groups, the neighborhood's Black population dropped more than 40% between 2000 and 2020, to 2,600, while the number of white residents shot up 178% to 2,150.

The Rev. Willie F. Ford Jr., pastor at St. Matthew Community Missionary Baptist Church in Miami's historically Black Coconut Grove, poses in the sanctuary on June 15. ‘If you haven't been here in a while, you don't recognize where you are,' Ford said. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

The Rev. Willie F. Ford Jr., pastor at St. Matthew Community Missionary Baptist Church in Miami's historically Black Coconut Grove, poses in the sanctuary on June 15. ‘If you haven't been here in a while, you don't recognize where you are,' Ford said. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

The Rev. Willie F. Ford Jr., a Grove native who leads one of the neighborhood's churches, has an apt phrase to describe what's happening. The West Grove, he said, has become "surrounded by encroaching affluence."

"If you haven't been here in a while, you don't recognize where you are," said Ford, pastor at St. Matthew Community Missionary Baptist Church, one of half a dozen churches in the neighborhood. "They're trying to slowly, progressively get the whole area."

CONFLUENCE OF FACTORS PROMPT NEIGHBORHOOD EXODUS

The dynamics are complex.

Entirely surrounded by two of Miami-Dade's wealthiest, priciest areas - suburban Coral Gables and the predominantly white portion of the Grove - West Grove's politically weak population and its expanse of relatively inexpensive, ideally situated land have made it increasingly attractive to lot flippers, speculative home developers and the city's seemingly inexhaustible supply of luxury home buyers.

At the same time, many residential and commercial properties have been up for grabs. Some longtime homeowners lost their properties, some encumbered by reverse mortgages, to foreclosure during the 2008 U.S. economic crash, or sold because they could not keep up with home repairs. Many other longtimers have died, leaving their aging homes to children and other heirs, many of whom gladly take purchase offers from developers in the six figures, sums many never dreamed of seeing.

Though the offers sound generous, some critics caution they're sometimes low-ball amounts, especially given the multimillion-dollar prices some of the new homes command.

Because the money isn't enough to buy new homes in West Grove, most of the sellers end up leaving, usually for other historically Black enclaves in South Miami-Dade County far from Miami

Those homeowners who remain, many of them elderly people in their 70s, 80s and even 90s, say they find themselves fending off relentless pressure to sell from real estate agents and brokers who call, email, drop off fliers or even come knocking on their doors daily. Some residents complain the tactics verge on predatory.

"It's offensive. It's disgusting," said Nichelle Haymore, who now lives in a West Grove house owned by her mother, Denise Wallace, herself a Grove native who also intends to return once she retires from her job as general counsel at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee.

Futuristic luxury townhomes rise along Day Avenue in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Thursday, June 16, 2022. The mostly low-income West Grove community is disappearing amid rapid residential redevelopment. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Futuristic luxury townhomes rise along Day Avenue in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Thursday, June 16, 2022. The mostly low-income West Grove community is disappearing amid rapid residential redevelopment. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

But such die-hards like Haymore and herself are increasingly rare exceptions, said Clarice Cooper, another Grove native, activist and grandchild of Bahamian immigrants. Cooper said she has refused "off-the-chain" overtures of as much as $1.2 million for her modest home. She noted that even that amount would not get her anything comparable in the Grove, given inflated prices and the fact her property taxes would rise significantly should she buy anew. That's something she can't afford on a retiree's fixed income.

"We have history here, like a long history," said Cooper, 72, whose mother and aunt, veteran activists Leona Ferguson Cooper and Leona Cooper Baker, respectively, live nearby in the west end of West Grove that sits within the boundaries of the neighboring city of Coral Gables. "My family has been here more than 100 years. We aren't just passing through.

"In my case, if I sold, where would I go?"

ELDERLY HOLDOUTS PLAN TO PASS HOMES TO CHILDREN

Even the churches aren't spared. Ford said he routinely fields, and rejects, inquiries from real estate agents. His church is the youngest of the Grove's congregations - three others are older than 120 years, among the earliest established in Miami. And like its peers, St. Matthew remains a vital community backbone. But the churches survive only because so many who left the neighborhood come back every Sunday for worship, Ford and other pastors say.

In Ford's case, that's most of his membership of just under 100 people, he said.

Ford, 47, said it's important for the churches and their congregations to hold on in the historic community. After leaving for college, never intending to return, Ford felt called back to the Grove and became pastor nine years ago

"I believe it was a choice that God made for me," Ford said. "It's no longer the community you grew up in. You don't have that sense of community anymore. But there is always something to be saved or preserved. My purpose is to assist this community and this congregation to be a beacon of life and hope."

Some of the holdout homeowners say they hope their children will take over once they pass.

Wilson Williams, 90, a retired Sears maintenance worker, poses on the porch of his longtime home in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Wednesday, June 15, 2022. Nonprofit group Rebuilding Together is installing new impact windows at Williams' house. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Wilson Williams, 90, a retired Sears maintenance worker, poses on the porch of his longtime home in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Wednesday, June 15, 2022. Nonprofit group Rebuilding Together is installing new impact windows at Williams' house. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Wilson Williams, 90, came south from Marianna, in northern Florida, as a young man to search for a steady job. He found it at Sears, where he worked in maintenance, first at the chain's Coral Way store and later in Hialeah. After a stint in Liberty City, in 1960 he bought his Grove home, where he and his late wife raised two daughters in peace and tranquility, he said.

"People came here to make some money. They moved here for a better life. Some found it, some didn't," he said. "I'm blessed."

He has willed the house to his daughters, who don't live in the Grove but visit frequently. He hopes they, or maybe his grandchildren, will want to keep it, but the choice is theirs, Williams said.

The neighborhood, he conceded, has changed "tremendously." And though the new white residents are friendly enough, he said, it's not the same neighborliness he used to enjoy. Black residents are being pushed "out of sight," he said.

"People don't see us anymore," Williams said. "I think people here are being pushed out. Underprivileged people, they can't afford these new buildings. Lots of people here love the Grove. You feel at home when you're in the Grove. It's being forgotten. They gotta bring it back."

But he stressed he has no intention of leaving. And to make sure longtime residents like Williams can stay, a nonprofit group, with backing from the city of Miami and private foundations, has embarked on a project to repair 100 homes belonging to low-income, elderly residents.

Last month, a contractor hired by Rebuilding Together Miami-Dade, a Grove-based nonprofit that pays for house repairs for low-income, elderly homeowners, installed impact windows at Williams' house so he can remain there in safety through the annual hurricane season.

"For now, I'm going to be home," he said, while sitting on his front porch, shaded by the thick canopy of a small city park next door, Coconut Grove Heritage Garden. "We're on a quiet street. That's what I love so much."

Ann Waiters, 92, a retired nurse, trims the hedge in the front yard of her longtime home in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Ann Waiters, 92, a retired nurse, trims the hedge in the front yard of her longtime home in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

His neighbor Ann Waiters, 92, said she's equally determined to stay. A widow and retired Mercy Hospital nurse, she has eight children, none in the Grove. One daughter has already agreed to take over the house once she passes - but no sooner, Waiters said.

"I have only a few years left, so I might as well enjoy the neighborhood," Waiters said, as she took clippers to the hedge in her front yard in 90-degree heat, pausing briefly to glance up at the roof, which she noted she needs to finish painting.

WEAPONIZING BUILDING CODE COMPLAINTS

Relations between Black residents and white newcomers to the Grove aren't always neighborly, though.

Last month, when Miami officials revived the neighborhood's Goombay Festival, a street celebration of Bahamian food, music and culture that once drew thousands of people from across Miami-Dade to West Grove, the event drew hundreds of overwhelmingly Black attendees to a neighborhood park - and a spate of noise complaints to the city, mostly from new residents, local activists say.

More consequently, according to activists and Miami Commissioner Ken Russell, whose district includes most of the Grove, new residents and developers are known to file code-violation complaints against longtime residents' homes, sometimes for minor or cosmetic issues. Deliberately or not, that can effectively force out elderly, poor residents if they can't afford fixes or mounting fines, Russell said.

"The weaponizing of code complaints has been an issue," Russell said, adding that some developers look for homes with code violations or liens because those owners may be more apt to sell. "Once those homes are fined or get liens filed against them based on a broken window, it becomes a burden for homeowners. Then a predatory process begins."

A Mocko Jumbie stilt walker dances to the music of the Junkanoo band during a parade at the Coconut Grove Bahamian Goombay Festival at Elizabeth Virrick Park in Coconut Grove on Sunday, June 12, 2022. SAM NAVARRO Special for the Miami Herald

A Mocko Jumbie stilt walker dances to the music of the Junkanoo band during a parade at the Coconut Grove Bahamian Goombay Festival at Elizabeth Virrick Park in Coconut Grove on Sunday, June 12, 2022. SAM NAVARRO Special for the Miami Herald

The neighborhood's many renters have even less security than homeowners.

The once ample supply of inexpensive apartments and duplex rentals in West Grove has all but dried up. Most of the old concrete monsters on Grand, for instance, have been condemned as hazardous by the city or demolished by developers and speculators who buy out longtime owners, some of them reputed slumlords who long exploited their tenants.

Only a couple of new buildings, both of them subsidized housing for seniors built by Miami-Dade County, have gone up to replace them.

A massive new project by a private developer, Platform 3750, is under construction on county land, and partly with county financing, at the corner of Douglas Road and U.S. 1. It will provide 78 affordable apartments, along with the neighborhood's first Starbucks and an Aldi discount grocery store.

The county's housing agency is also seeking bids to redevelop a low-density public housing property it owns in the Grove to add both affordable and market-rate rental homes, and in addition it plans to expand the Gibson Plaza senior housing development on adjacent land on Grand Avenue, Miami-Dade housing director Michael Liu said.

But Liu acknowledged a common complaint from Grove residents: That because of federal regulations, the income-restricted units can't be reserved for the locals, but must be made available countywide. That means that, given Miami-Dade's demographics, most of the occupants of county housing in the Grove are Hispanic. Residents of projects to be redeveloped are guaranteed a spot at the new mixed-income communities, but no one else.

"We are sensitive to that issue," Liu said, suggesting that one alternative is for local community leaders to actively prepare and recruit residents to apply as the new units become available.

A pair of century-old wood-frame cottages still stand in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Thursday, June 16, 2022. The mostly low-income community is disappearing amid accelerating gentrification. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

A pair of century-old wood-frame cottages still stand in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Thursday, June 16, 2022. The mostly low-income community is disappearing amid accelerating gentrification. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Those being displaced as apartments and duplexes come down, and lucky enough to get some city assistance with relocation, are encouraged to go elsewhere because of the lack of housing in the Grove, said Carolyn Donaldson, a Grove native and activist who serves as vice chair of Grove Rights and Community Equity Inc., or GRACE, an umbrella organization of local churches and civic and community groups that pushes for equitable development.

ABSENTEE LANDLORDS LET APARTMENT BUILDINGS DECAY

That redevelopment in the Grove is inevitable has long been clear, Donaldson said. But the city did virtually nothing to help residents stay in the neighborhood, she said.

"You have to question whether the city's actions contributed to the gentrification," said Donaldson, who now lives in Miami Lakes but commutes to the Grove nearly every day for church and volunteer work. "For the people who were receiving assistance, that seemed to be available if they moved to other historically Black communities. It wasn't anything like, ‘We're going to do something and provide opportunities for you to stay in the Grove.'

"A lot of promises have been made to the community over the years, and very few have come into fruition," she said. "The question that needs to be asked more is, ‘What happens to the people? Where do they go? What do they do?' "

Making the crunch far worse, owners of the rentals that are left are jacking up rents, taking advantage of the severe housing shortage afflicting South Florida, said Ashley Snow, development director of Rebuilding Together, the group helping locals fix their homes. A typical three-bedroom house in the neighborhood that not long ago rented for $1,500 a month, for example, is now going for as much as $5,000, Snow said.

"It's getting wild, and people can't afford to go somewhere else, either," she said.

A vacated, condemned apartment building is one of the last standing along Grand Avenue in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Thursday, June 16, 2022. The West Grove community is disappearing amid rapid gentrification. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

A vacated, condemned apartment building is one of the last standing along Grand Avenue in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Thursday, June 16, 2022. The West Grove community is disappearing amid rapid gentrification. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Some of the blame, the Rev. Ford said, goes to mostly absentee landlords who failed to maintain their properties over decades, charging cheap rents to keep apartments occupied. Once the buildings were condemned, the tenants were left high and dry, he said.

"They're not going to be able to come back. Even if people wanted to come back, before we even talk about pricing, there are no buildings to come back to," said Ford, who lives in the Grove with his family. "It's a sad thing. It was a very cultured place. But now the culture is no longer there. The people are no longer there. It's a whole different community."

EFFORTS TO REVIVE GRAND AVENUE COMMERCE FAILED

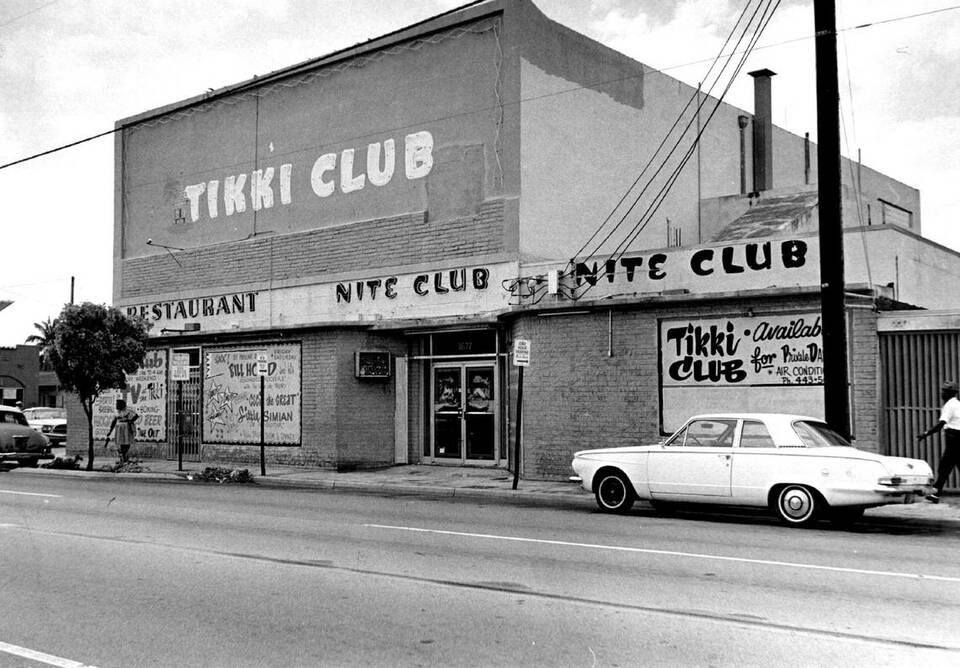

Meanwhile, the Grand Avenue businesses that depended on the vanished residents, including markets, cafes, bars, entertainment venues like Tikki Club and Gil's Spot and neighborhood landmarks such as the Range Funeral Home, have evaporated with them. Because several redevelopment schemes along Grand have failed to bear fruit, in part because of financing difficulties, the storied street is today mostly a veritable ghost town of vacant, fenced-off lots and boarded-up buildings, with a few exceptions. Local owners have renovated a handful of apartment buildings, one of which has a store called Polished Coconut selling hip vintage items on the ground floor.

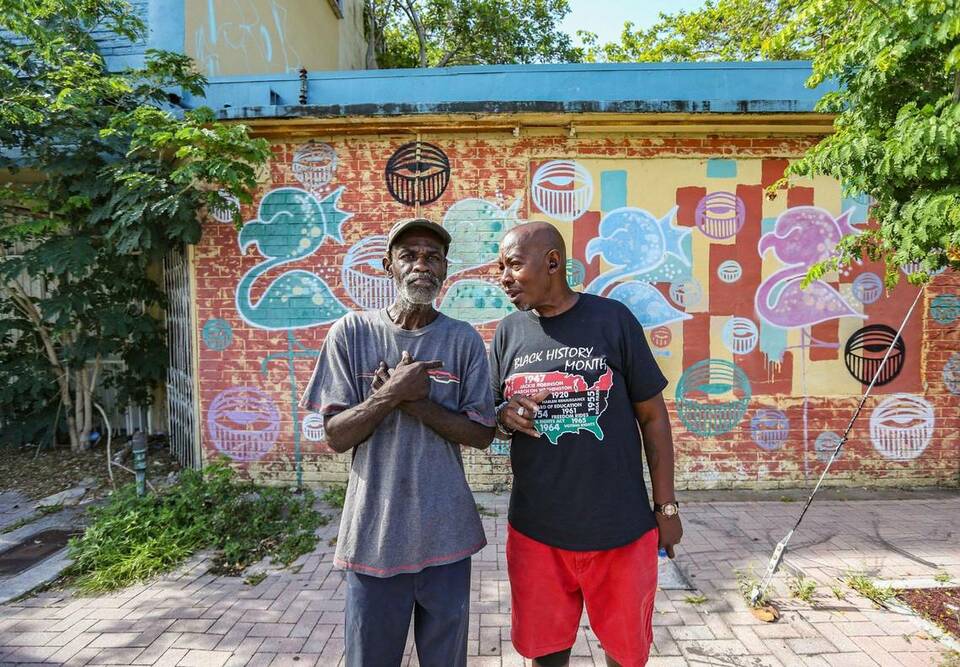

Lifelong residents Michael Williams, 63, and Randy Russ, 67, stand in front of the shuttered Tikki Club on Grand Avenue in the western section of Miami's Coconut Grove neighborhood on Thursday, June 16, 2022. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Lifelong residents Michael Williams, 63, and Randy Russ, 67, stand in front of the shuttered Tikki Club on Grand Avenue in the western section of Miami's Coconut Grove neighborhood on Thursday, June 16, 2022. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

A cluster of newer shops built by Grove developer Andy Parrish in 2004 occupies one corner of the "four corners" neighborhood gateway at Douglas and Grand, including a printing and copy business and a high-end mattress store, but like the vintage shop those don't really cater to the locals.

Parrish, who also built several affordable homes in scattered lots across West Grove, said he and his partners sold the shops in 2015 after becoming frustrated that the city did nothing to help revive the street. For one thing, he contends, zoning rules that require far more parking than can be feasibly built on the shallow lots on Grand Avenue have made it impractical and financially impossible for anyone to redevelop on Grand, but the city has declined to address the issue for years.

Now, he said, there's little of the historic community left to save.

"We had to bail out," said Parrish, known as a community-minded developer. "We couldn't get anything done. It's disgraceful, a story of city incompetence. It's all gone up in smoke."

YOUNGER GENERATION SOLD OUT

The history of broken redevelopment promises extends to a formerly publicly owned lot once earmarked for affordable housing in a Bahamian style in the Coral Gables section of the Grove.

As that plan and a subsequent vision for a restaurant fell through, the Gables instead approved a plan from a developer who jointly controls the long-vacant property with a local homeowners association for a gas station - the same thing that was on the lot decades ago. But construction on the planned Wawa convenience store with gas pumps has been in legal limbo since parents from the adjacent Carver Elementary School sued over dangerous traffic and pollution they say the Wawa would produce. The city said in January it was going back to the drawing board after a judge called the plan "blatantly illegal."

Until Platform 3750 opens, around the end of the year, that means the only businesses catering to West Grove are a beauty salon, two convenience stores and Charles Barber Shop, a mainstay on Grand whose owner declined to be interviewed because he said the neighborhood is "over" and there's little to talk about.

Warren "PeeWee" McNealy, 63, sells barbecue ribs and chicken from the back of his truck along Grand Avenue and Hibiscus Street in Miami's Coconut Grove on Thursday, June 16, 2022. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Warren "PeeWee" McNealy, 63, sells barbecue ribs and chicken from the back of his truck along Grand Avenue and Hibiscus Street in Miami's Coconut Grove on Thursday, June 16, 2022. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

The only purveyors of food or drink on Grand are Queen Supermarket, a corner convenience store that serves as a default gathering spot for locals, and Grove fixture Warren "PeeWee" McNealy, who has been serving up tender, smoked barbecue ribs and chicken from the back of his pickup truck at the corner of Hibiscus Street for more than a decade.

On the corner outside Queen, Grovites often set up camping chairs on a cracked sidewalk under a shade tree to chat, catch up and argue.

Calvin Williams, a retired restaurant cook who stops by almost every afternoon, and buddy William Love, a retired truck driver, recall when there was much more to Grand Avenue - restaurants and cafes, clubs, movies at the ACE Theater, even tailors who made custom suits.

"It was booming at one time," said Love, 75. "You could buy anything you wanted. You even had tailor-made clothes. You didn't have to leave the Grove. The people spent their money in the community."

Williams, 72, was blunt: "It was beautiful then. Not no more."

Love and Williams said they both came to the Grove as children, brought from Georgia by their parents, who like many other African-American Southerners sought a better and freer life than the Deep South offered after World War II.

They plan to stay, though Love complained his house is now "surrounded by high-rises" - a description that alludes to the fact that the new homes and duplexes are so large they tower over the wood and concrete homes built in decades past.

Calvin Williams, a retired restaurant cook and lifelong resident of Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove, sits on the back of his truck while chatting with friends outside a convenience story on Grand Avenue and Plaza Street on Wednesday, June 15, 2022. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Calvin Williams, a retired restaurant cook and lifelong resident of Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove, sits on the back of his truck while chatting with friends outside a convenience story on Grand Avenue and Plaza Street on Wednesday, June 15, 2022. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

But Williams, whose own son lived in the Grove but passed away, said succeeding generations share in the blame for the historic neighborhood's obliteration. "The younger generation, they sold out," he said. "The community's out of here, the original people, I mean."

One developer whose banners and massive new homes adorn many a block in West Grove said what he builds in the neighborhood responds to market demand and zoning rules long in place. Berk Boge, CEO of Three-Minute Record Development, said developers are not to blame for the shrinking Black demographic there.

"The people who have been renting are the most affected," Boge said, before adding: "It doesn't make anyone happy. But what has the city done about it? It's not fair to blame developers for everything that has happened to the people displaced. It's a socioeconomic issue."

Boge, who lives in the Grove and has been building in the historically Black section for more than two decades, said it's just business.

"It's no different than any other part" of the city, he said. "People want modern, so developers build modern. Developers always give people what they want. If you look at the new homes, it's like comparing an old car to a newer car. You can't compare the new homes to the old ones. If people want size, then that's what I need to do."

Grand Avenue, once the thriving commercial heart of Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove, stands mostly vacant on Friday, June 17, 2022. The Black community is disappearing amid real estate speculation and rapid gentrification. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

Grand Avenue, once the thriving commercial heart of Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove, stands mostly vacant on Friday, June 17, 2022. The Black community is disappearing amid real estate speculation and rapid gentrification. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

ECONOMIC DISPARITY, LACK OF POLITICAL CLOUT TAKE TOLL

It all comes down to land appeal and value, said Miami historian Marvin Dunn, a social psychologist who raised his family in West Grove before moving to the suburbs once he retired from Florida International University's faculty. Now white home buyers, squeezed out of other nearby areas as prices and demand for luxury housing skyrocket, come to the West Grove looking for what has long drawn people like him to the neighborhood - but in the process they're destroying what made it special.

And it's nothing short of tragic, he said.

"It was just absolutely a beautiful enclave of culture and music and food that made it a distinctive and unique community in the country," Dunn said. "It was the trees, the fruit trees, the fact that the community had a great umbrella of trees. The environment, the way that people took care of their properties, it was a very different time and a very attractive place to live - one of the literally coolest places to live in Miami."

Dunn, who chronicled the neighborhood's early history in his classic "Black Miami in the Twentieth Century," said the economics, and the split in the community it's provoked, have doomed historic West Grove, which lacked the unity and political clout to fight back.

A view of a thriving Grand Avenue just east of Douglas Road in the historically Black section of Miami's Coconut Grove in an undated old file photo. Bob East Miami Herald

A view of a thriving Grand Avenue just east of Douglas Road in the historically Black section of Miami's Coconut Grove in an undated old file photo. Bob East Miami Herald

But he also traces the beginning of the neighborhood's downfall to integration and the end of Jim Crow laws in 1965, which allowed those who wanted to leave to do so. Many did decamp for the suburbs or newer majority-Black communities, in particular middle-class families with the means to buy homes elsewhere, leaving the poorest or oldest residents behind.

"I think the West Grove is past the tipping point," Dunn said. "Part of the difficulty politically is some Blacks favor selling the land and getting as much money as possible for it. And who can blame them? The Black community is not unified on how to protect itself, so it's going to be very difficult to stop the inevitable march of the white pillboxes, even though they are antithetical to what the West Grove has been and represents. But money talks.

"It will be gone. It's like losing an arm or a leg and you can't get it back. It's irreplaceable."

BAHAMIAN IMMIGRANTS BUILT COCONUT GROVE BUT WERE SEGREGATED

That distinct history stretches back to the 1880s, when Bahamian immigrants joined white settlers to build the fledgling village of Coconut Grove and, a few years later, Miami itself. Bahamian Grove residents provided much of the city's workforce in its earliest days, and even many of the signatures required for its incorporation in 1896.

But hardening segregation meant they could not live in white neighborhoods, attend the same schools or go to the movies, or later theatrical productions, at the Coconut Grove Playhouse. Bahamians helped build the playhouse which backs onto historic Charles Avenue, West Grove's original main street.

The Rev. Theodore Gibson, a Miami civil rights leader, plants a U.S. flag on one of the four corners at Douglas Road and Grand Avenue in the historically Black section of Coconut Grove during a Memorial Day ceremony in an undated file photo. Bob East Miami Herald

The Rev. Theodore Gibson, a Miami civil rights leader, plants a U.S. flag on one of the four corners at Douglas Road and Grand Avenue in the historically Black section of Coconut Grove during a Memorial Day ceremony in an undated file photo. Bob East Miami Herald

Over decades to come, as African Americans from the Deep South looking for opportunity settled in the Grove alongside Bahamians and their progeny, the neighborhood developed a thriving, self-contained economy that included wealth, middle-class stability and deep poverty - and a strong identity as a hub of Black culture and activism.

Among its most prominent figures was the Rev. Theodore Gibson, a Bahamian-born minister and civil rights activist who fought to desegregate Miami in the 1960s as head of the local NAACP and who went on to serve nine years on the city commission.

Until integration came, said Cooper, the Grove activist, she could not go to a performance at the playhouse. But though the legal line was erased, de facto segregation persisted, she noted. White residents did not cross into the West Grove except to drive through, even after the end of Jim Crow, she said.

"Back then, if you saw a white person walking around the neighborhood, it was the mailman," she joked.

The separation meant West Grove was often deprived of basic public investment - Charles Avenue remained unpaved for years and there was no running water in the neighborhood until the 1960s, for instance - and the neighborhood served as a dumping ground for some noxious uses.

Old Smokey, a city incinerator in Coconut Grove's historically Black west section that belched toxic ash over the neighborhood for 45 years until it was shut down by federal order in 1970, is seen in an undated file photo. Bob East Miami Herald

Old Smokey, a city incinerator in Coconut Grove's historically Black west section that belched toxic ash over the neighborhood for 45 years until it was shut down by federal order in 1970, is seen in an undated file photo. Bob East Miami Herald

One of the most notorious: Old Smokey, a city incinerator just off Grand Avenue that belched toxic ash over neighboring homes and schools from 1926 until it was shut down in 1970 by federal action. Residents filed a lawsuit involving health claims stemming from the incinerator, including possible cancer clusters, based on research by the Environmental Justice Center at the University of Miami's law school. The suit is ongoing.

RENEWED HOPE OF REVITALIZATION

Given the backdrop of neglect and decline, it's no surprise so many longtime residents have seized the opportunity to leave, said Haymore-Kearney, one of the sisters who came back to the West Grove after years away pursuing higher education and a professional career. It's the same story that's happening in gentrifying historically Black neighborhoods across the country, she said.

"You have people who had a community once, but with redlining, bad schools, crime and drugs, it's hard for people to maintain it. So I'm not faulting the people who did sell," Haymore-Kearney said. "But when it happens repeatedly, you begin to lose the character of a neighborhood. I don't think that's any different in Washington, D.C., in Harlem or in Watts in LA. It's an all-American story, unfortunately."

But she and her family are among those still fighting to save some of the neighborhood's heritage. Haymore-Kearney returned for good three years ago, moved into an apartment owned by her family and enrolled her son at Carver Elementary, the historic neighborhood school.

Now she works in a nonprofit, promotes yoga and wellness and is assisting her family with an ambitious plan to restore and reopen the historic ACE Theater, the Grove's Jim Crow-era movie house, as a cultural and community center. Her grandfather, Harvey Wallace, a prosperous West Grove businessman, bought the ACE after it closed in the 1970s, but could not get bank financing to realize his plans to expand and reopen it.

Haymore-Kearney said there's now some hope for West Grove thanks to the broadening realization of what could be lost, and a growing willingness from some public officials and the federal government to support preservation and equitable redevelopment efforts in historically Black neighborhoods. For instance, the ACE Theater Foundation has received two grants for renovation totaling nearly $900,000 from the National Park Service.

The Tikki Club, a popular nightclub, was a landmark for years on Grand Avenue in the heart of the historically Black western section of Miami's Coconut Grove. Long vacant, the building still stands near the corner of Douglas Road. Miami Herald file

The Tikki Club, a popular nightclub, was a landmark for years on Grand Avenue in the heart of the historically Black western section of Miami's Coconut Grove. Long vacant, the building still stands near the corner of Douglas Road. Miami Herald file

Community organizations like long-running Home Owners and Tenants Association, or HOATA, the more recently formed organization of churches and civic organizations pushing for equitable development and the Ministerial Alliance, a group made up of neighborhood pastors and church congregations, have pushed to protect tenants' and homeowners' rights with the aid of UM law professors and students. They have also pressed developers planning new commercial projects to offer "community benefits" such as funding or meaningful participation to locals.

There's also the prospect of new, privately developed affordable housing. An affiliate of the Urban League of Greater Miami called New Urban Development has acquired a lot off Grand Avenue and reached an agreement to develop several adjacent vacant plots with United to Survive. It's an ownership group made up of members of prominent neighborhood families, including the Gibsons, that bought the land more than two decades ago, but has been unable to build anything on it. The idea would be to build both residential and commercial uses, the mix Grand once had in plenitude.

New Urban, which has completed several senior and affordable-housing projects across the county, is also working on a plan to build housing on land owned by West Grove churches.

By putting locals in the driver's seat, the approach would preserve residents' stake in the neighborhood in the face of outside developers that New Urban president Oliver Gross said exploit West Grove property owners.

"The question is, how do you develop in these communities where someone gives you some nominal amount for your land, and we never see or hear from you again?" Gross said. "Some people call it gentrification. I think it's a natural transformation because of the economic fundamentals. But the void is that people who are indigenous to those neighborhoods are not benefiting.

A luxury home with a rooftop deck looms over modest working-class homes at the corner of Elizabeth Street and Frow Avenue in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Thursday, June 16, 2022. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

A luxury home with a rooftop deck looms over modest working-class homes at the corner of Elizabeth Street and Frow Avenue in Miami's historically Black West Coconut Grove on Thursday, June 16, 2022. Al Diaz adiaz@miamiherald.com

"They are being bowled over, disregarded, pushed out. I think Coconut Grove is a poster child for this in terms of how it's happening in such a robust fashion."

The second question, Gross said, is financing. Given high construction costs, building truly affordable housing requires public subsidies, he said. The city and county, he said, "have to be prepared to put their money where their mouth is."

IS COMMUNITY REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY KEY TO COMEBACK?

The city has belatedly responded.

In March of last year, at the prompting of Russell, Miami commissioners approved the creation of a West Grove community redevelopment agency, or CRA, that would channel a portion of property taxes from new development into affordable housing and other neighborhood improvements. A CRA in Miami's Overtown, for example, has leveraged a development boom that's generated millions in new tax revenue to help engineer a marked turnaround in that historically Black neighborhood's once-desolate center.

Because the funding would not be subject to federal rules, CRA-supported projects could put Grove residents first, Russell said. Several landowners, churches and Grove developer Peter Gardner, who with partners controls numerous lots, have said they're interested in participating, and would build in the local island style and scale rather than big white boxes, Russell said. Gardner, who comes from an old-line white Coconut Grove family, did not respond to a request to be interviewed for this story.

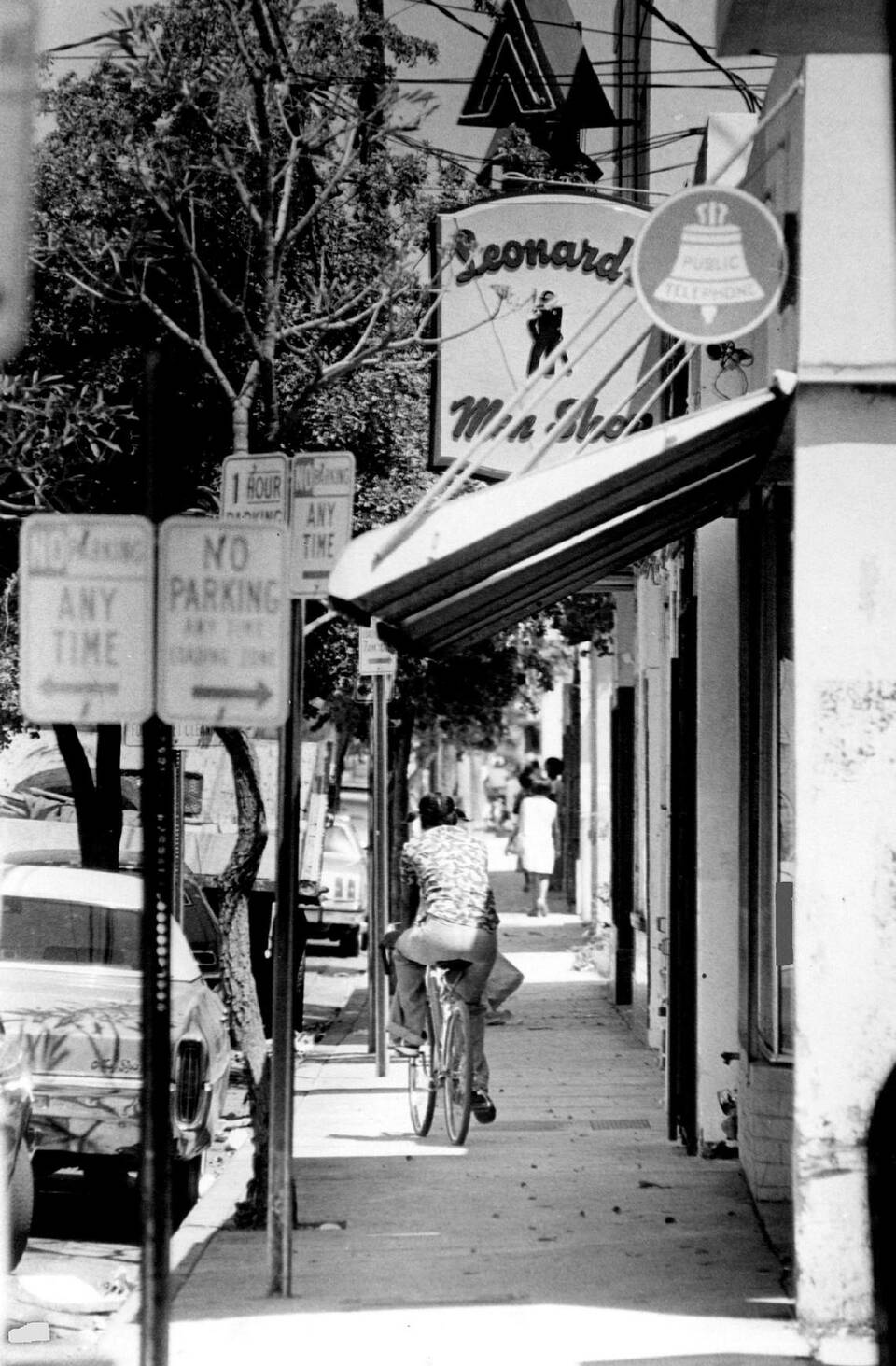

Grand Avenue was long the commercial heart of the historically Black section of Miami's Coconut Grove. A sign for a long-gone men's tailor shop is visible above the sidewalk cyclist. Miami Herald file

Grand Avenue was long the commercial heart of the historically Black section of Miami's Coconut Grove. A sign for a long-gone men's tailor shop is visible above the sidewalk cyclist. Miami Herald file

The West Grove Community Redevelopment Agency requires final approval from Miami-Dade commissioners, who have voted heavily in favor in the past.

"The CRA is the greatest potential reparation for this community," city commissioner Russell said. "Everybody knows it. It should come across the line.

"But Miami-Dade Commissioner Raquel Regalado, whose district includes the Grove, said she won't support creation of the CRA. It would take years to accrue enough money to make a difference, and the community can't wait that long, she said. Without Regalado's support, it's likely the plan will be bottled up indefinitely.

"What's happening in the West Grove, like other historic communities throughout the county, is accelerating in real time," Regalado said in a prepared statement. "I don't think we have that kind of time. You can see the march of the sugar cubes on almost a weekly basis."

Instead, Regalado said faster solutions will come through Miami-Dade's blueprint for redeveloping and expanding county housing sites in the neighborhood. Legislation to be voted on this summer by the Miami-Dade Commission would allow county-owned land close to transit stations, like much of the West Grove is, to be rezoned for higher density.

"I'm committed to working with the City of Miami and the churches, community organizations and residents of the West Grove to build and support projects that will increase affordable housing without harming the character of the neighborhood," Regalado said.

Russell, who must leave office at the end of the year because he's running for Congress, is also pushing other initiatives, including officially renaming West Grove as "Little Bahamas of Coconut Grove." After years of planning, the city is embarking on a $6.5 million project to rebuild the popular swimming pool at Elizabeth Virrick Park in the West Grove, which Russell pushed.

He's also supporting community groups in negotiations with a developer who wants to build an office building on one of the Douglas Road four corners. The developer, Andale, needs a zoning break to accommodate parking. The community organizations want a commitment to include affordable housing in another future project the developer is planning nearby. So far, though, the developer has not agreed, said Cooper, president of the homeowners and tenants group.

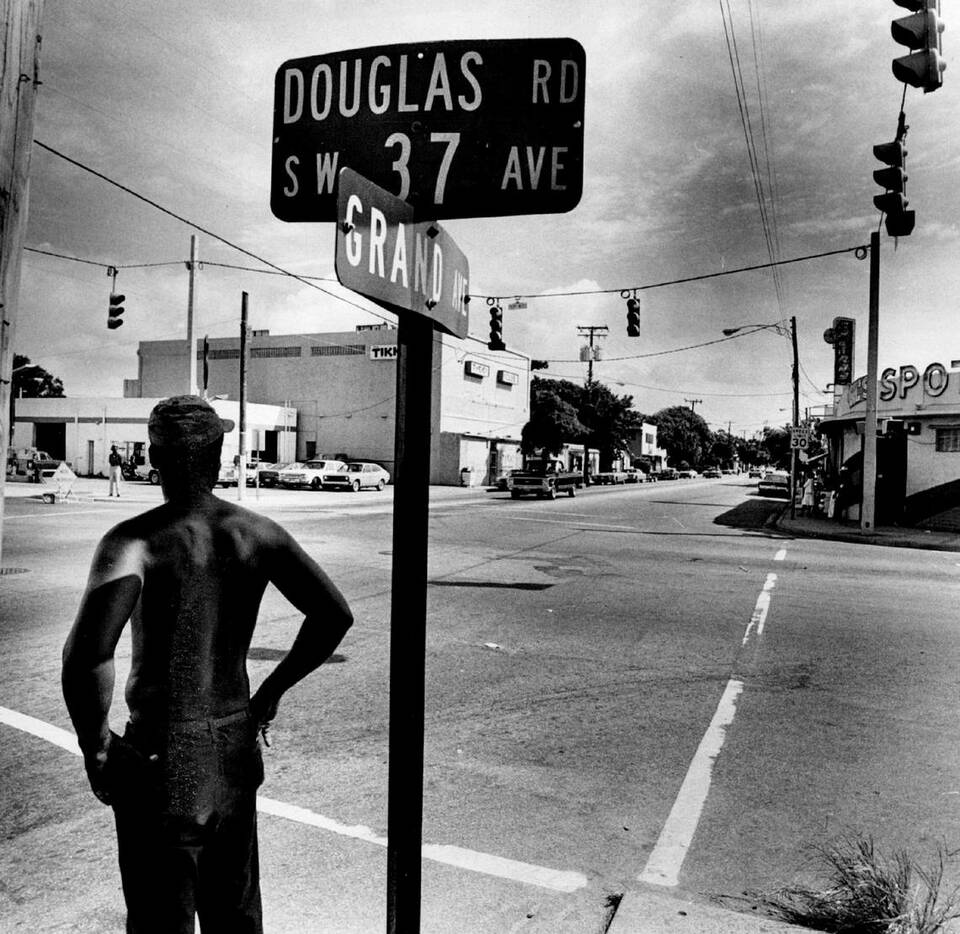

A view of the four corners intersection at Douglas Road and Grand Avenue in the heyday of the historically Black western section of Miami's Coconut Grove shows the Tikki Club just past the street sign at left and Gil's Spot on the right. Joe Rimkus, Jr Miami Herald

A view of the four corners intersection at Douglas Road and Grand Avenue in the heyday of the historically Black western section of Miami's Coconut Grove shows the Tikki Club just past the street sign at left and Gil's Spot on the right. Joe Rimkus, Jr Miami Herald

"Skepticism is warranted," Russell said, before adding: "There is still a very strong opportunity for this community to thrive.

" West Grove natives and community activists Cooper and Donaldson say they're still willing to hold out hope, but they remain wary of relying on city promises. A controversial redistricting plan that carved up Coconut Grove, once the province of a single city commissioner, among three districts went through in spite of strong opposition from residents in both the historically Black and white sections. That will only further lessen the West Grove's clout, Cooper said.

The delay in CRA approval doesn't inspire confidence, Donaldson said.

"We thought the CRA was going to be a shoo-in when it went to the county," she said. "A lot of work has gone into it. There have been community meetings, and a lot of input as to what we wanted. So what is the holdup?"

Even if any of the city or county initiatives do come to pass, Cooper noted, it will be years before the neighborhood sees any benefits. And she fears by then it may be too late for West Grove.

"It's still a hard fight. Everything is an issue. Everything is an argument, even if someone has good intentions," Cooper said. "What we're trying to do in the community is hang on, hang in there. But getting back to where it was 40, 50 years ago, that's not going to happen.

"People like me, the die-hards like myself, will we even be around to see the fruits of any of this?"

Miami Herald reporter Daniel Oropeza contributed to this report. This story was originally published July 10, 2022 6:15 AM

Read more at: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/coconut-grove/article262373827.html#storylink=cpy