| dd |

|

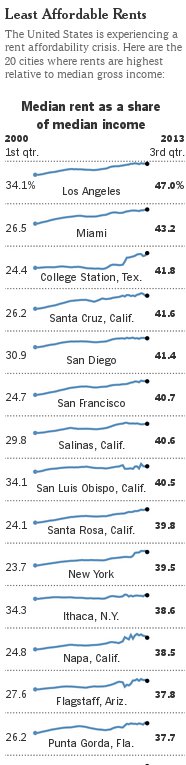

In Many Cities, Rent Is Rising Out of Reach of Middle Class

MIAMI — For rent and utilities to be considered affordable, they are supposed to take up no more than 30 percent of a household’s income. But that goal is increasingly unattainable for middle-income families as a tightening market pushes up rents ever faster, outrunning modest rises in pay.

The strain is not limited to the usual high-cost cities like New York and San Francisco. An analysis for The New York Times by Zillow, the real estate website, found 90 cities where the median rent — not including utilities — was more than 30 percent of the median gross income.

In Chicago, rent as a percentage of income has risen to 31 percent, from a historical average of 21 percent. In New Orleans, it has more than doubled, to 35 percent from 14 percent. Zillow calculated the historical average using data from 1985 to 2000.

Nationally, half of all renters are now spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing, according to a comprehensive Harvard study, up from 38 percent of renters in 2000. In December, Housing Secretary Shaun Donovan declared "the worst rental affordability crisis that this country has ever known."

Apartment vacancy rates have dropped so low that forecasters at Capital Economics, a research firm, said rents could rise, on average, as much as 4 percent this year, compared with 2.8 percent last year. But rents are rising faster than that in many cities even as overall inflation is running at little more than 1 percent annually.

One of the most expensive cities for renters is Miami, where rents, on average, consume 43 percent of the typical household income, up from a historical average of just over a quarter.

Stella Santamaria, a divorced 40-year-old math teacher, has been looking for an apartment in Miami for more than six months. "We’re kind of sick of talking about it," she said of herself and fellow teachers in the same boat. "It’s like, are you still living with your mom? Yeah, are you? Yeah." After 11 years as a teacher, Ms. Santamaria makes $41,000, considerably less than the city’s median income, which is $48,000, according to Zillow.

Even dual-income professional couples are being priced out of the walkable urban-core neighborhoods where many of them want to live. Stuart Kennedy, 29, a senior program officer at a nonprofit group, said he and his girlfriend, a lawyer, will be losing their $2,300 a month rental house in Buena Vista in June. Since they found the place a year ago, rents in the area have increased sharply.

"If you go by a third of your income, that formula, even with how comfortable our incomes are, it looks like it’s going to be impossible," Mr. Kennedy said.

Part of the reason for the squeeze on renters is simple demand — between 2007 and 2013 the United States added, on net, about 6.2 million tenants, compared with 208,000 homeowners, said Stan Humphries, the chief economist of Zillow.

That trend is continuing as young people and doubled-up families move out on their own. "They’re creating a lot of incremental demand," Mr. Humphries said. But new households rarely plunge straight into homeownership, especially given that mortgages are much harder to obtain than they were before the financial crisis. "The expectation is that when they strike out into their own units they’ll be moving into rental as opposed to the owner side," he said.

And as rents head hig

her in the tightest markets, many are discovering that living on their own is proving unaffordable, forcing them to double up again. Arturo Breton, a 37-year-old waiter in Miami Beach, said that after years living on his own, he was joining forces with a roommate who works as a manager at J. C. Penney. "I’ve come down to the conclusion that in this country, it’s easier for two people to pay the rent than for one person," he said.

her in the tightest markets, many are discovering that living on their own is proving unaffordable, forcing them to double up again. Arturo Breton, a 37-year-old waiter in Miami Beach, said that after years living on his own, he was joining forces with a roommate who works as a manager at J. C. Penney. "I’ve come down to the conclusion that in this country, it’s easier for two people to pay the rent than for one person," he said.

For many middle- and lower-income people, high rents choke spending on other goods and services, impeding the economic recovery. Low-income families that spend more than half their income on housing spend about a third less on food, 50 percent less on clothing, and 80 percent less on medical care compared with low-income families with affordable rents, according to a new report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition. And renters amass less wealth, even non-housing wealth, than homeowners do.

The problem threatens to get worse before it gets better. Apartment builders have raced to build more units, creating a wave of supply that is beginning to crest. Miami added 2,500 rental apartments last year, and 7,500 more are expected in the next two years, according to the CoStar Group, a real estate research firm.

But demand has shown no signs of slackening. And as long as there are plenty of upper-income renters looking for apartments, there is little incentive to build anything other than expensive units. As a result, there are in effect two separate rental markets that are so far apart in price that they have little impact on each other. In one extreme case, a glut of new luxury apartments in Washington has pushed high-end rents down, even while midrange rents continue to rise.

"Increasing the supply is not going to increase the number of affordable units; that is a complete and utter fallacy," said Jaimie Ross, the president of the Florida Housing Coalition. "People say if there really was a great need, the market would provide it; the market would correct itself. Well, the market has never corrected itself and it’s only getting worse."

Money for affordable housing has dried up at a time when it is needed most. Federal housing funds, in a form now known as HOME grants, have been cut in half over the last decade. The percentage of eligible families who receive rental subsidies has shrunk, to 23.8 percent from 27.4 percent, the Harvard study found. And Florida, which like other states faced large budget shortfalls after the financial crisis, has raided its housing trust fund, funded by a real estate transfer tax, for several years running. This year, the Legislature has proposed restoring at least part of the money.

Cities have been left to address the problem on their own, with some granting exceptions to their own zoning laws to allow for things like micro-apartments. Miami has allowed some variances to its urban plan for projects like Brickell View Terrace, which will have 176 units in a prime location near a Metrorail station. Ninety of the units will be affordable for people making 60 percent of the median income, 10 for people making less, and the rest will be market rate.

But a seemingly insatiable demand for luxury condos in Miami, created in part by wealthy Latin Americans, has caused land prices to soar, making affordable housing projects harder to build anywhere close to downtown. Moving farther out is cheaper, but the cost savings on housing can be quickly wiped out by transportation costs. A 2012 study by the Center for Housing Policy found that Miami was the most expensive metropolitan area in the country when housing and transportation costs were combined.

In many markets, buying a home is considerably cheaper than renting, and Miami is no exception. But many people are shut out of buying because their income is too low, they don’t qualify for a mortgage or they are burdened by other debt. In 2008, a quarter of rental applicants were still paying off student loans, according to CoreLogic, but as of last fall half of them were doing so.

Steve Gunn, 25, the marketing director for a Miami real estate brokerage firm, said he could certainly afford an apartment on his salary of $52,500 — if he weren’t paying more than $800 a month in student loan debt. Instead, he commutes 90 minutes to work. From his mother’s house.